I was just thinking about what I should highlight this week when I came across something that I couldn’t resist scanning and writing about immediately. When most people envision archives, they think of old stuff (the terms “dusty” and “musty” are used so frequently in articles about archives that a Tumblr has gone up to document these instances). With the Information Age in full swing, however, many archivists are working with much newer (and more voluminous) collections. Despite the fact that I’ve worked almost exclusively with 20th century materials over the course of my career, most of the records I’ve handled have still been years or decades older than me. My background in history allows me to appreciate and have a better understanding of documents related to World War II or the Civil Rights Movement, but I don’t get hit with nostalgia when I rifle through these types of documents.

Part III has a plethora of records from the 1980s and ’90s, though, so sometimes I’ll come across references to events or cultural phenomena that I can personally recall. There are certain things that shape your life and change the world around you – things that you remember with clarity and detail. Some take place over a very short time – just a moment, or a number of hours. Almost anyone alive in America during the Kennedy assassination, the Columbine school shootings, or September 11th can tell you exactly what they were doing and where they were when they found out about these events. Other important cultural events last longer, with hard-to-pinpoint start and end dates, and sometimes you don’t realize until years later just how important they were. Such was the case with the beginning stages of public access to the World Wide Web.

My family first got a computer and access to the internet in 1994. We used a dial-up modem (these things made the most glorious sounds), which means we connected to the internet through our phone line. We didn’t have a second line just for the internet, so whenever someone was on the phone, we couldn’t also be online. At first we used AOL and CompuServe to connect, but eventually we signed on through a local BBS that charged us a whopping $99/year for unlimited access. I used IRC and ICQ (precursors to AIM, Google Talk, and even the Facebook chat feature) to talk to new and old friends, and learned very basic HTML to post on message boards. I remember Angelfire and GeoCities websites, with their questionable color schemes and animated gifs, with fondness. Does all of this sound like gibberish to you? If so, then you’re either a) much younger than me, or b) much less nerdy. I praise my nerdiness, though, because it has helped me immensely: learning basic HTML early (even though I didn’t really understand what I was learning) meant that it was intuitive to me when I spent time learning it more purposefully later in life. Because I spent so much time online in the early stages of the internet, I was able to delve into it in a way that is difficult to do now – everything is so much more user-friendly these days. I’m grateful that I have a deeper understanding of it than I might have if I’d waited to connect. The world is a different place now – there are more ways to search for, exchange, and disseminate information than ever before. It is now considered more abnormal to not have a Facebook profile than it is to meet a romantic partner online. A global community (or multiple global communities, if you want to think of it that way) exists in a way that would never have been possible a few decades ago. The internet is no longer new and mysterious, but it’s still exciting, and still awesome in the truest sense of the word.

But what does all of this have to do with the ACLS collection? What did I find that led me to travel down this Memory Lane? Why, nothing less than a printout of the very first ACLS website! Before I get to that, though, let’s take a moment to look at a memo from former ACLS Vice President Douglas Bennett requesting that a number of staff members put together a “World Wide Web site” for the organization. This was in 1995, when many companies and organizations did not yet have websites – but that shouldn’t surprise you, since the ACLS has a history of embracing technology. And just look at that list of women in the “To” field!

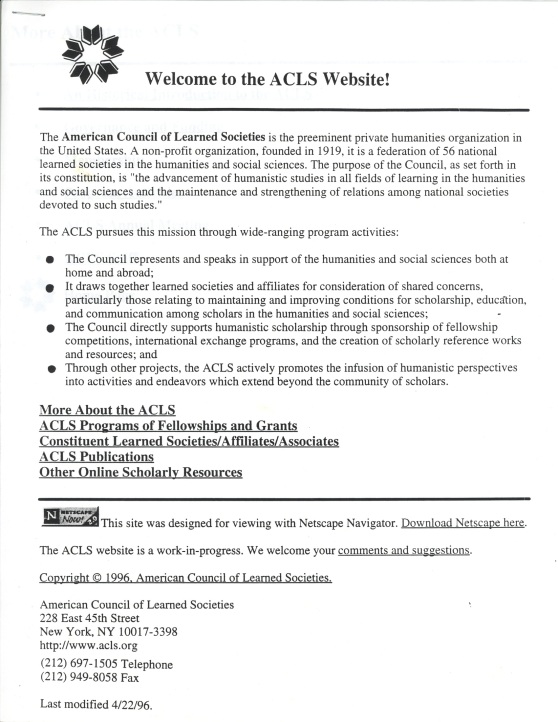

What did they come up with? Here’s a printout of the very first ACLS website, dated April 22, 1996. This basic homepage highlights the organization’s mission, giving the reader a basic introduction to the ACLS. There are links to pages where one can learn more about the organization, their grant and fellowship programs, their constituent societies, their publications, and outside scholarly resources – in short, it had a lot of the same types of information that are available on the ACLS website today, which means this web development team started off really well! If you want to see early versions of the site in a browser as they were designed to be seen, head on over to the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine, where doing a search for acls.org allows you to view captures of the site dating back to 1997! Feel free to click around and see how the site has changed over the years.

I especially love the note about the website being designed for Netscape Navigator (in fact, that little button was the very thing that brought back waves of memories for me), an early web browser which has since been replaced by Internet Explorer, Mozilla Firefox, Google Chrome, Safari, Opera, and a number of other browsers.

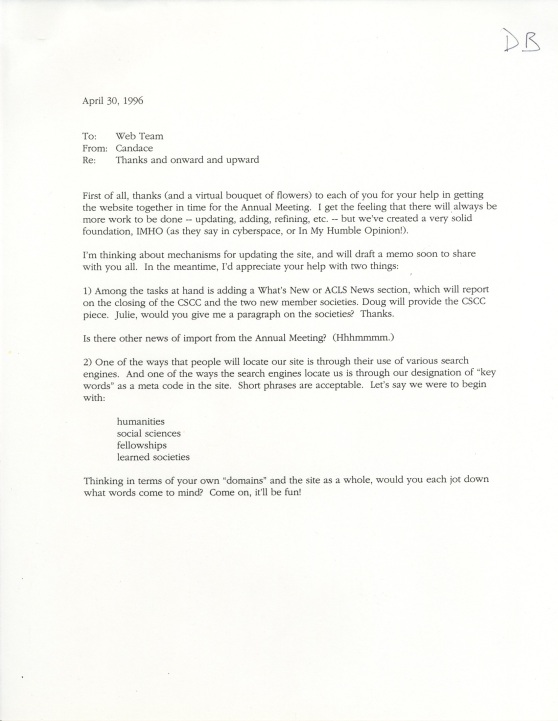

The final document I’d like to share with you is a memo written by Candace Frede, the current Director of Web and Information Systems at ACLS (wonder how she ended up there?):

Indeed, there is always more work to be done when it comes to websites. I love Candace’s use of internet slang in this message (slang that’s still used today!), and the bit about how to get search engines to recognize the site, which currently continues to be an important part of building any website. Descriptive metadata for the win (or ftw, for you other internet nerds out there)!